Heavy, immobile and commonplace, a bench is one of those objects that one seldom looks at. Our eyes, drawn towards those things that actively invite our attention, slide past it. The exhibition, The Bench : A Microscopy, shifts the focus. It moves the bench from the periphery to the centre of attention and interrogates its relationship, and ours, with its urban and rural surroundings. It also investigates the importance of underlying immaterial structures, such as the ways in which we move around. This project, inspired by Michael Jakob’s book, Poétique du banc, was set up in France in 2016 in the L’Onde art centre in Vélizy-Villacoublay and the Graineterie art centre in Houilles. Initially, the bench was viewed primarily as an object that the individual would appropriate for quiet introspection and contemplation. In a subsequent phase, it was rather its capacity for social interaction with others which was put under the magnifying glass. This exhibition retains these earlier aspects, but adds a new perspective that explores specifically the territory of Brussels.

Free entrance

In 2008, a study was published based on the mental map of Brussels of about thirty young people who all lived in the city but came from different geographical and social backgrounds. It revealed a network of imaginary barriers reflecting the way in which they took possession of and moved about their urban spaces. Behind the visible, cosmopolitan city appeared an invisible compartmentalised city, its inhabitants enclosed within their neighbourhoods, prevented by the power of their perceptions from wandering into another’s space. Ten years later, one might wonder how much of this has changed. How is Brussels perceived? How does one take ownership of a neighbourhood and along which routes? How does one interpret and share these routes? And most importantly how does one add to them? If one observes the city from one of its benches, at what point does it cease to oscillate between an image which is sometimes hostile and sometimes welcoming? How is this image reinforced or contradicted by the bench’s own shape and the posture that it proposes or imposes upon us? Here we will not be given an unambiguous answer; only an inducement to discover for ourselves Brussels as we have never before known it. The available tools will vary: Jean-François Pirson and Jean-Christophe Quinton, in their different ways, suggest a map; Francesca Chiacchio proposes a game, a tableau of a sundial and benches from which to contemplate the sunset every day of the year.

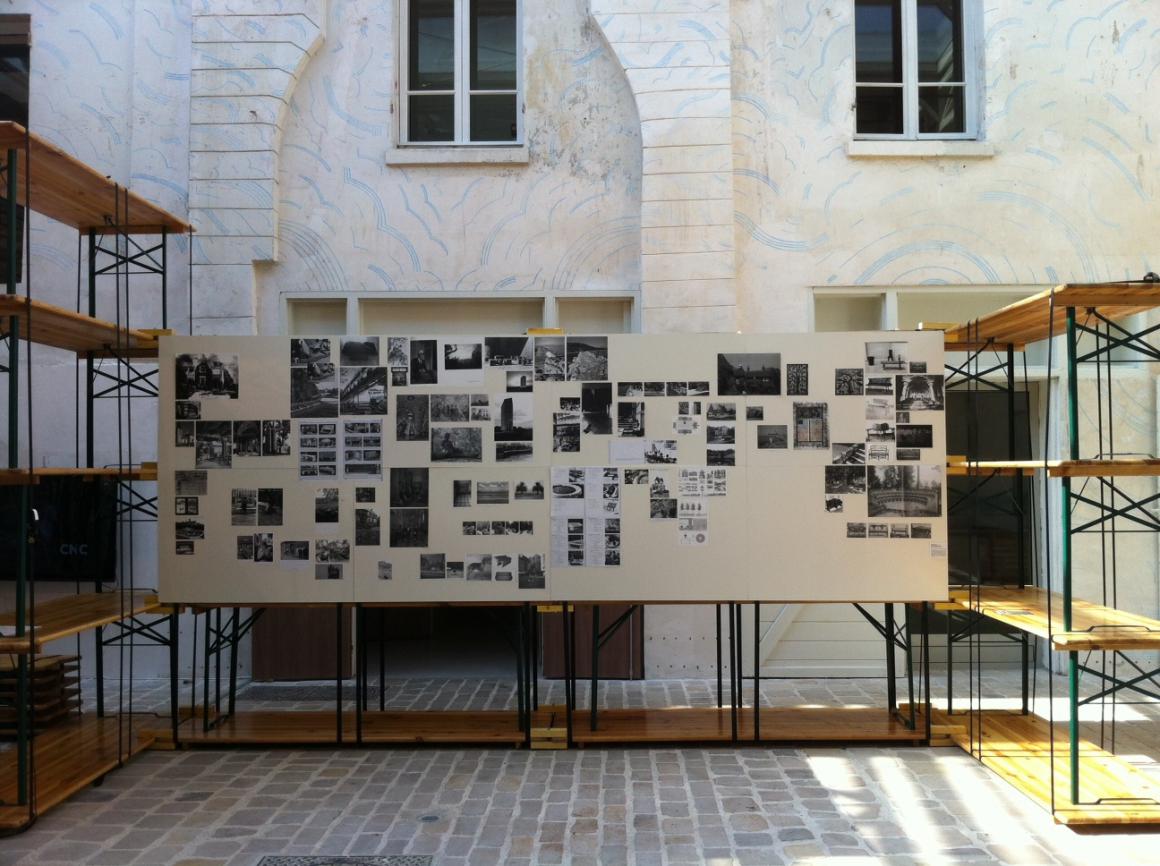

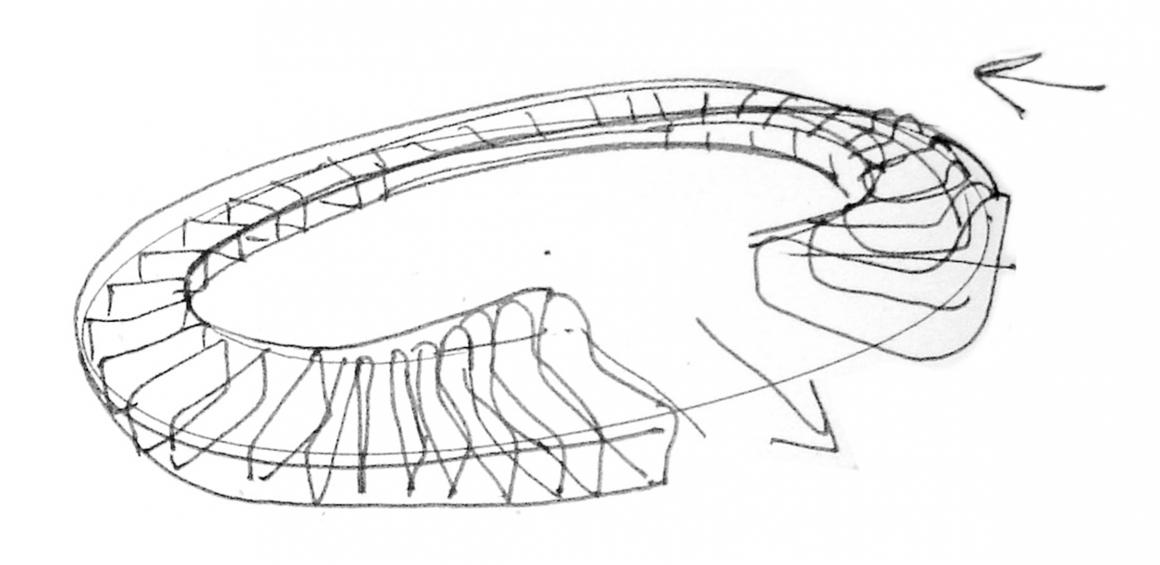

The exhibition is conceived of as a stroll through the grounds of the CIVA Foundation, with stopping places at the benches of Simon Boudvin, Francis Cape, Ann Veronica Janssens, muller van severen and Julien De Smedt. An exception to the rule is the Cabinet des Absents, a room containing hundreds of benches taken from different places and times in the form of an archive, to which visitors may add benches from the archive of their own recollections. Depending on which route one chooses, the tour will start, end or be interrupted by a film, The Social Life of Urban Spaces (1988). Its author, William H. Whyte, suggests that what makes the bench so captivating for the observer is the bizarre behaviour that it gives rise to. Some people seek out the busiest of places to satisfy their need for solitude, some sit close up to others even when there is enough space to sit apart, while others, as a group, might prefer to sit on a low, easily accessible step, so that everyone else has to walk around them.

One might conclude that the insignificance of the bench has less to do with its form, which is infinitely variable, than with its primary function of giving the body some rest. When looking back on life, who would take account of those spare moments when one did nothing? The spirit of our age only values activity and disregards time spent doing nothing. In this system of accounting, sitting on a bench doesn’t even earn a mention. Nevertheless, although one cannot properly include it in one’s life’s work, it is no less important in making life worthwhile. Literature abounds with meditations and revelations to oneself or a companion, eagerly awaited or quietly summoned in thought; brief moments of lucidity arising from that little belvedere, the humble bench.