free entrance

Is a library a place for reading or rather a place for socializing, studying, working, training... full of books? And how can it be activated to reach a new public? In these times of uncertainty in the face of our world’s evolution in the Anthropocene era, with the continuous extension of the fields of knowledge and their complex intricacies, the many alternative proposals and the few momentary certainties, a library can no longer be a "temple of knowledge" that gives answers. Above all, it is a space for exchange, proposing documents, a place to live and activities that all contribute to enriching our reflection on our ways of living in the world, of understanding what surrounds us, such as the city of yesterday, today and tomorrow.

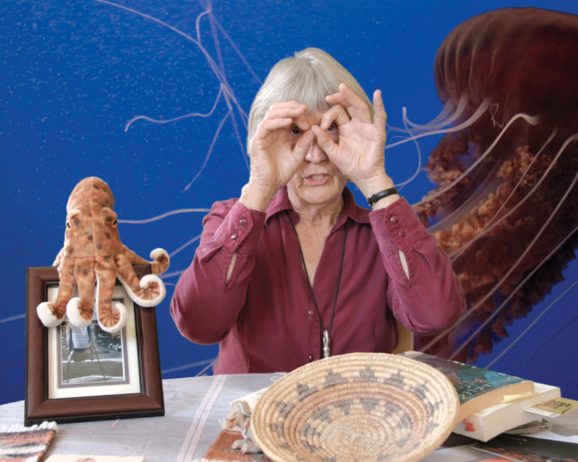

In order to offer a real plurality of choices, the library will be participatory by adopting various methods of mediation: book selections (10 books by) by architects, scientists, philosophers, urban planners, artists, among others; with for some of them a public presentation of their choice (La bibliothèque à bords perdus: Chapter X), open call to the public to feed a section of books to be exchanged, donated or suggested, etc. Consequently, thanks to a system of adding, exchanging and reclassifying its contents, the library will be transformed a little bit every day, giving the public a different experience with each visit.

The incongruity of this temporary presence constitutes a rich field of exploration for the world of ideas, as well as the promise of future survival within the setting designed by the architects of Atelier Kanal.

Inhabiting the World

Thanks to the disciplines it covers - architecture, urban planning, landscape and urban ecosystems - the CIVA library is a privileged place to reflect and explore the notion that imprints our intimate link to space: inhabiting the world.

How has humankind perceived and designed its living space through the ages? Since when have we been aware of the impact that this founding act can have on our environment? What could well be the founding narratives that have supported cities? Are we writing new ones to engage the future? Urban sprawl or metropolis? An inclusive city or exclusive neighbourhoods? A place for everyone to live in? Including the other living beings that make up our urban landscape? Centipedes, foxes and spiders too? Dandelions, lettuce and rhododendrons?

The end of dominant ideologies and of the major anthropocentric narratives has gradually made way for another way of understanding inhabited territories, made up of a series of intertwined stories, of which the singularity of the layers (and the strength of the propositions they carry) is sometimes difficult to grasp. It is a palimpsest that we have inherited, which we must ‘deal with’ in order to continue moving forward in a constructive reflection whose main interest will be precisely to recognize the potential value of what already exists.

That is the narrative that is being written now, and whose main challenge is to be able to formulate ideas that are both clear and intelligible, provided that they are able to bear witness to the richness of the multiple arrangements that make up our world. Within a broader conception of what exists, it is a question of being able to notice, produce and accept new, at times antagonistic or contradictory realities – without refusing to get involved and without drowning them in a murky consensus. For example, the dual question of the Anthropocene (a social question: how are we humans to act?) and resilience (a material question: what to do with that which exists already?) will become essential to the necessary evolution of the inhabited environment. How can we manage today this antagonism against which we are ontologically deprived?

The description of the cities and landscapes that make up our environment has explored a range of registers in recent decades in order to be able to account for their great diversity. All styles and iconographies have been summoned in order to describe their multiple facets.

There was, for instance, the Strada Novissima at the 1980 Venice Biennale (underlining the interest in a return to the European city that Léon Krier and Maurice Culot, among others, advocated), preceded slightly by the continuous cities and planetary infrastructures imagined by the radical Italian, English and Austrian groups (little more than a short decade separates them).

Shortly before, the proposal put forward by Colin Rowe in his book Collage City championed the idea of an exemplary coexistence between the classical models of urban composition organized by the open spaces of the city (squares and boulevards, i.e. everything that makes up the ‘void’ of cities) and the modernist visions of an environment defined by its own architectural objects (the surrounding spaces resulting from ‘full’ operations).

There were also reflections on an urbanism almost exclusively linked to the car: the potential for the development of an art of constructing the city through the repurposing of codes linked to the emerging Pop culture – Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steve Izenour with their book Learning from Las Vegas.

More recently, citizen participation has dominated the conversation, while in parallel there emerged the idea of a responsible reflection on the future of the planet, in view of the unprecedented damage caused to the natural environment: the question of the Anthropocene. And in the latter months, it is the health crisis that has revealed to us through a magnifying glass the resilience (real or supposed) of our cities, and the problems of social and environmental inequality.

How then can we continue to think about the question of the built environment as a whole, given that it seems to be made up of so many different realities, all of which are also the bearers of a project whose relevance is often exciting? How can we describe the reality of a single world by reading its multiple existences?